Looking At/As Trans

As the increasingly divisive 2016 U.S. election cycle heated up, one of the most contentious debates in several states’ legislatures, on the national stage, and in online social media spaces concerned the use of public restroom facilities by transgender people. In the months following the repeal of the anti-discrimination Houston Equal Rights Ordinance (HERO) and the passing of North Carolina’s anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) House Bill 2 (HB2)—actions fueled in part by defamatory anti-transgender advertisements (Solomon, 2015; Young, 2015)—LGBTQ allies in the political, entertainment, and business sectors made various efforts in their support of basic human rights for transgender people. Some actions, such as the National Basketball Association’s (NBA) decision to move the 2017 All-Star Game (Bontemps, 2016; Peralta, 2016; Zillgitt, 2016) from North Carolina as well as other entertainment (Kludt, 2016) and business expansion (Waliga, 2016) cancellations due to HB2 show unambiguous support for LGBTQ rights.

However, other allies took different approaches to show their support for trans people during this time of highly publicized and highly politicized “bathroom bill” debates. Although well-meaning, some messages were created on mainstream and/or social media and hastily shared without critical consideration for the impact those messages carry about transgender communities. As trans scholar Valérie Clayman (2016) wrote, “Mass media and social media have been happily accepting the ‘any representation is good representation’ politic even as many trans activists and bloggers have written extensively on the problematic nature of the moving images they consider to be trans” (p. 102). However, Clayman’s untransing the image in which the transgender viewer diminishes personal identification with harmful representations of trans people (2016) is not easily accomplished when those representations are frequently and repeatedly assigned to trans communities. The theory does not remove the social or political effects of the harmful representations. Instead, visually literate trans people and allies must continue to challenge the problematic harmful trans representations in moving and still images circulated in mass media and social media.

This section will look at the author’s engagements on social media about three artivist visual messages[1] and how attempts to bridge communities through them instead created tension within trans communities and between trans people and allies. These tensions arose out of reinforced negative stereotypes as well as dispositions centered on visual aliteracy that stemmed from the “‘any representation is good representation’ politic” (Clayman, 2016, p. 102).

However, other allies took different approaches to show their support for trans people during this time of highly publicized and highly politicized “bathroom bill” debates. Although well-meaning, some messages were created on mainstream and/or social media and hastily shared without critical consideration for the impact those messages carry about transgender communities. As trans scholar Valérie Clayman (2016) wrote, “Mass media and social media have been happily accepting the ‘any representation is good representation’ politic even as many trans activists and bloggers have written extensively on the problematic nature of the moving images they consider to be trans” (p. 102). However, Clayman’s untransing the image in which the transgender viewer diminishes personal identification with harmful representations of trans people (2016) is not easily accomplished when those representations are frequently and repeatedly assigned to trans communities. The theory does not remove the social or political effects of the harmful representations. Instead, visually literate trans people and allies must continue to challenge the problematic harmful trans representations in moving and still images circulated in mass media and social media.

This section will look at the author’s engagements on social media about three artivist visual messages[1] and how attempts to bridge communities through them instead created tension within trans communities and between trans people and allies. These tensions arose out of reinforced negative stereotypes as well as dispositions centered on visual aliteracy that stemmed from the “‘any representation is good representation’ politic” (Clayman, 2016, p. 102).

They OD’d on the Rhetoric

|

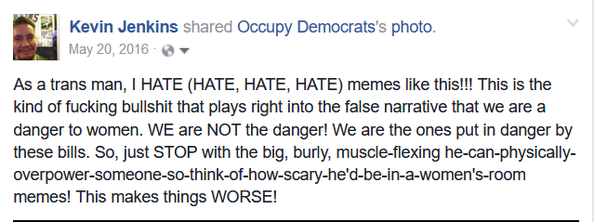

A meme created and posted May 19, 2016 on Facebook and Twitter by the political grassroots organization, Occupy Democrats, quickly made the rounds on social media. The image depicts four well-muscled female-to-male models (one man is shown twice side-by-side) under the caption, “These are all transgender men. Republicans want laws to force them to use the bathroom with your sisters and daughters. Let that sink in…” (Occupy Democrats, 2016). I was already frustrated by having seen numerous similar memes championed online and on cable news shows at various times in the preceding year. I held lengthy discussions with other leaders in the local trans community about this continuing problem. I wanted to dissuade my social media contacts from further distributing this meme and allow a space to discuss the pitfalls of these visual messages. Thus, I shared the meme publicly on my Facebook wall with the following status update which garnered 36 emoji reactions from likes and loves to angry faces and 27 comments, some of which were dialogues with a few Facebook friends.

|

This limited exposure on my wall is in contrast to the over 60,000 shares, 25,000 reactions, and 3,400 comments on the Occupy Democrats’ original post but which held numerous exchanges between users similar to the ones on my post with several elucidating on its harmful representations of trans people in general, and trans men specifically (Alejandro, 2016; Baker, 2016a, b, c; King, 2016a, b; Muscato, 2016, Pratt, 2016a, b). Others argued in favor of the meme, often debating with other allies, citing assumed intention and personal interpretation as having greater importance for critique and even overlooking any possible harmful effects (Bowers, 2016; DeBlasi, 2016a, b; Musick, 2016; Pacia, 2016a, b).

For example, Kaitlynn Marie Baker (2016a) commented, “I just thought of something. This is implying that our sisters and daughters wouldn't be safe with these men. And that's just as fucked up as the republican standpoint.” Delia Marie Pacia (2016b) replied,

For example, Kaitlynn Marie Baker (2016a) commented, “I just thought of something. This is implying that our sisters and daughters wouldn't be safe with these men. And that's just as fucked up as the republican standpoint.” Delia Marie Pacia (2016b) replied,

|

I think the intent can be twisted to say that this is promoting the false idea that Transgender people are sexual predators, but I think the original intent behind this message was that these people look like men and therefore should go to the men's room.

|

Another such exchange occurred between Scott Pratt and Marya DeBlasi. Pratt (2016b) commented, “Occupy Democrats - Your editors must be brain dead. smh Is this supposed to support transgender people or imply that they are are dangerous?”

DeBlasi (2016b) replied, “Read Very Carefully, and you maaaay be able to work that question out.”

Pratt (2016a) retorted, “And if you ...very carefully... ask a few Republicans, they would tell you that it proves their delusional point.... FAIL. As in FAIL a 3rd grade persuasive writing assignment.”

When interviewed for an article that champions Occupy Democrats’ meme generation and circulation as the pinnacle of successful information distribution, co-founder Rafael Rivero states about the effectiveness of memes, “The meme must tell the full story. You can’t assume people know anything. You have to be able to tell the entire story in as few words as possible. You have to plug into the zeitgeist” (Jarvis, 2016, para. 8). However, this meme does not tell a full story. And when challenged about its harmful effects, the creators are dismissive (Occupy Democrats, 2016b). With nearly 7.5 million followers on Facebook, the Occupy Democrats’ platform is much greater than even famous trans activists such as Laverne Cox or Caitlyn Jenner. Thus, the memes created by Occupy Democrats are capable of circulating virally. Writing or creating memes concerning a population about whom so few have any knowledge is to speak for that population and shape the discourse in intentional and unintentional ways. It is dangerous for allies to hastily plug into the zeitgeist on an issue of human rights when their own knowledge is lacking about the issue or the group affected. To do so further harms the very population allies claim to support. After creating and distributing an artivist meme, Occupy Democrats quickly moves on to the next hot topic, plugging into the zeitgeist and cranking out memes without sustained relationships with or input from those communities of whom and for whom they speak in bold all-cap fonts[2].

DeBlasi (2016b) replied, “Read Very Carefully, and you maaaay be able to work that question out.”

Pratt (2016a) retorted, “And if you ...very carefully... ask a few Republicans, they would tell you that it proves their delusional point.... FAIL. As in FAIL a 3rd grade persuasive writing assignment.”

When interviewed for an article that champions Occupy Democrats’ meme generation and circulation as the pinnacle of successful information distribution, co-founder Rafael Rivero states about the effectiveness of memes, “The meme must tell the full story. You can’t assume people know anything. You have to be able to tell the entire story in as few words as possible. You have to plug into the zeitgeist” (Jarvis, 2016, para. 8). However, this meme does not tell a full story. And when challenged about its harmful effects, the creators are dismissive (Occupy Democrats, 2016b). With nearly 7.5 million followers on Facebook, the Occupy Democrats’ platform is much greater than even famous trans activists such as Laverne Cox or Caitlyn Jenner. Thus, the memes created by Occupy Democrats are capable of circulating virally. Writing or creating memes concerning a population about whom so few have any knowledge is to speak for that population and shape the discourse in intentional and unintentional ways. It is dangerous for allies to hastily plug into the zeitgeist on an issue of human rights when their own knowledge is lacking about the issue or the group affected. To do so further harms the very population allies claim to support. After creating and distributing an artivist meme, Occupy Democrats quickly moves on to the next hot topic, plugging into the zeitgeist and cranking out memes without sustained relationships with or input from those communities of whom and for whom they speak in bold all-cap fonts[2].

Stumbling in High-Heel Boots

North Carolina’s discriminatory “bathroom bill,” HB2, in part requires people to use public restroom facilities based on sex designation on their birth certificates, thereby forcing transgender people to use those facilities counter to their gender identities if their birth certificates have not been amended. In contrast to the numerous cancellations of entertainment and sporting events, singer and longtime LGBTQ advocate Cyndi Lauper decided to keep her Raleigh, North Carolina performance as scheduled (Portwood, 2016). For the occasion, she and Kinky Boots collaborator Harvey Fierstein rewrote the lyrics to one of the show’s songs and recorded a video with the cast (kinkybootsbway, 2016; Portwood, 2016; Wong, 2016). Like the Occupy Democrats meme, this artivist video rapidly went viral online, celebrated by many in the trans community and allies.

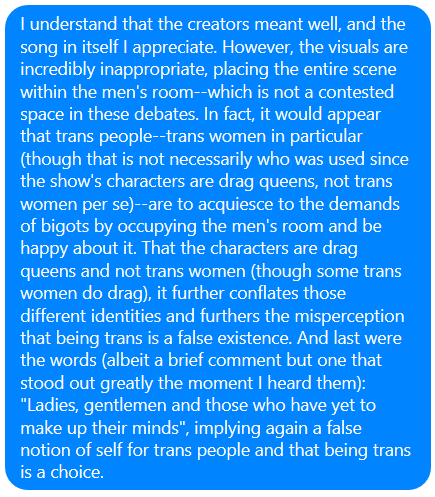

My Facebook news feed quickly filled with the numerous shares by friends on their own walls and by people in trans groups of which I am a member, often with multiple postings in the same group. Despite others’ joyous sharing and kudos to the creators, I was shocked by what I saw and heard in the video as the play’s cast in drag joyously sang and danced and simulated using urinals in a men’s bathroom. Wanting to ask it not be shared so quickly and to discuss why the video was a problem for the trans community, I was already overwhelmed by the number of postings; and I knew my concerns would be ignored much like before. The best I could do was provide an angry emoji reaction to indicate I found problems with the video. One young trans woman contacted me in a private message after seeing my reaction on a few different postings of the video, asking me to share why I disliked it. I answered,

My Facebook news feed quickly filled with the numerous shares by friends on their own walls and by people in trans groups of which I am a member, often with multiple postings in the same group. Despite others’ joyous sharing and kudos to the creators, I was shocked by what I saw and heard in the video as the play’s cast in drag joyously sang and danced and simulated using urinals in a men’s bathroom. Wanting to ask it not be shared so quickly and to discuss why the video was a problem for the trans community, I was already overwhelmed by the number of postings; and I knew my concerns would be ignored much like before. The best I could do was provide an angry emoji reaction to indicate I found problems with the video. One young trans woman contacted me in a private message after seeing my reaction on a few different postings of the video, asking me to share why I disliked it. I answered,

My friend thanked me and stated she had felt somewhat hurt when watching the video but was unsure if she should since so many mutual friends celebrated it. Her feelings are a valid reaction to what she saw and heard as are the celebratory reactions of those trans people who shared it because they found a sense of vicarious empowerment through it. This feeling of empowerment was certainly Lauper and Fierstein’s intention in offering what they felt was supportive (Portwood, 2016). However, the decision to “just pee where you wanna pee,” directed toward trans people is not to be taken as lightly as the song and dance number suggests. A trans woman may decide she will use the women’s bathroom despite laws prohibiting her entry; yet no matter how empowered she may feel to do so, she is still at risk of arrest, harassment and violence. And as Wong (2016) points out, the video depicts the cast “using a restroom at New York’s Al Hirschfeld Theatre together without incident” (para. 2). The problem with that is the majority of those in the video identify as men, even if wearing a dress, and are occupying the men’s room, which is how proponents of bills such as HB2 think of trans women and where they demand trans women pee.

It Doesn’t Run Both Ways

“Almost perfect” is the phrase that came to mind during the 2016 Summer Olympics when I saw Nike’s Unlimited Courage advertisement online, featuring the first openly transgender athlete, Chris Mosier, to compete for Team USA. In the ad, a disembodied voice introduces Mr. Mosier and announces his trans status before asking him a series of questions about competing for a place on the Olympic team while he trains in different settings. In the 40-second ad, it was the first question, “Hey, Chris, how’d you know you’d be fast enough to compete against men?” (Nike, 2016, 0:08) that prevented perfection to me. I experienced the ad as deflating and demeaning because the initial question removed Chris and all other trans men from the category of man. All Nike lacked in this commercial was one additional word, crucially placed, to have made the ad extraordinarily inspirational, and incredibly knowledgeable of the identity struggles of trans people, as well as respectful of trans people. Instead, they asked a question steeped in ignorance. This time, I took not only to Facebook to air my critique, but to Twitter as well since I knew I could tag the company in my posts. I retweeted their video and commented, “Dear @Nike, let me fix your omission for you: ‘How'd you know you'd be fast enough to compete against OTHER men?’” (Jenkins, 2016f) and followed that with another tweet, “@Nike, leaving out the word ‘other’ further othered us. #TransMenAREMen” (Jenkins, 2016g).

This seemingly simple omission places trans men in a position outside the category of “man,” which in a culture still heavily influenced by binary thinking, means “woman.” It flattens the experiences of trans men and trans masculine people. It reinforces notions that trans men must either be transitioning medically and be able to “pass” as a cisgender man to be included in the category of man, or that we will always fall short of that category even if transitioning or passing. In the video there is a young man several years in medical transition and passing, whose manhood is questioned and who is questioned about his manhood by framing the ad with the initial question.

Mr. Mosier and I had a brief amicable exchange on Twitter regarding the implications of this omission in the ad the following day (Jenkins, 2016e, h, i, j; Mosier, 2016a, b), to which he asserted he had reviewed the script prior to airing and that in any case, this media representation was not representative of the trans community but only of him (Mosier, 2016a). This is an odd assertion given that he recognizes he serves as a representative of his country as he competes in the Olympic Games and that he represents the trans community when held as an example of it commercially as a role model for youth (Rense, 2016). As one of the few in the trans community given a global platform from which to speak, and as one of the even fewer as a trans man in such a position, every detail counts in how thousands of others without such a voice are represented.

This seemingly simple omission places trans men in a position outside the category of “man,” which in a culture still heavily influenced by binary thinking, means “woman.” It flattens the experiences of trans men and trans masculine people. It reinforces notions that trans men must either be transitioning medically and be able to “pass” as a cisgender man to be included in the category of man, or that we will always fall short of that category even if transitioning or passing. In the video there is a young man several years in medical transition and passing, whose manhood is questioned and who is questioned about his manhood by framing the ad with the initial question.

Mr. Mosier and I had a brief amicable exchange on Twitter regarding the implications of this omission in the ad the following day (Jenkins, 2016e, h, i, j; Mosier, 2016a, b), to which he asserted he had reviewed the script prior to airing and that in any case, this media representation was not representative of the trans community but only of him (Mosier, 2016a). This is an odd assertion given that he recognizes he serves as a representative of his country as he competes in the Olympic Games and that he represents the trans community when held as an example of it commercially as a role model for youth (Rense, 2016). As one of the few in the trans community given a global platform from which to speak, and as one of the even fewer as a trans man in such a position, every detail counts in how thousands of others without such a voice are represented.

Implications

Selfie by trans US Air Force veteran, Carla Lewis, that went viral online. Reproduced with permission.

Selfie by trans US Air Force veteran, Carla Lewis, that went viral online. Reproduced with permission.

When allies decide they want to show their support by creating or sharing imagery and text about trans people, they first need input from trans people when making statements about them or speaking on their behalf. I must note, however, that I do not speak for trans people as a whole since there are many who favorably view the media I have critiqued here. Nevertheless, trans input in media is slowly beginning to happen in film and video production by employing consultants for shows like Transparent and with trans people producing their own shows on social media platforms such as Her Story on YouTube and Brothers on Vimeo.

But there is still a problem, perhaps a growing one, on social networking sites with the uncritical creation and spreading of memes. One of the latest flare-ups on Facebook concerned the “Klinger memes” in response to the president’s proposed ban on trans people serving in the military. Perhaps more people I know, whether trans or not, have spoken out against the Klinger memes. I have witnessed many online arguments and defriendings over them. Those in favor of the memes often see them as harmless fun that reference a beloved television character from M.A.S.H. Many are quick to point out Klinger’s fictional existence and the historical context of the show. Critiques of them reifying notions of the “man in a dress” trope used against trans women have been ignored in some cases but fortunately listened to in others. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine that one rather uphold their fondness for a fictional character of decades past than respect the needs of those who tell them of the verbal assaults they endure because of these depictions and of the discrimination, threats, and physical harm they face because of the trope it furthers. Instead, what should more widely circulate are positive representations of actual transgender service members, whether those in uniform or our veterans who wear a graphic t-shirt with the transgender symbol in a pink triangle above the statement, “Transgender Veteran: I fought for your right to hate me” (Equality House, 2016), which has to date approximately 99,000 reactions and 10,000 comments, whether positive or negative, as well as 191,514 shares on Facebook alone.

Allies should remember to listen when a trans person tells them that an image or text is damaging to the community and personally hurtful. A true ally will not demand justification when asked to not share or to remove a post. If an ally wants to learn why something circulating is problematic, wait. It does not take long for media outlets to explain in online articles; or at least give that friend who requested the removal or refrain from sharing time to recover from the pain before inquiring. They will likely volunteer an explanation on their own when they are ready. The trans community needs allies. But it needs allies who listen and who learn what we have to teach them about how to best provide allyship, which includes critically assessing the images and texts circulating on social media before hitting “share.”

But there is still a problem, perhaps a growing one, on social networking sites with the uncritical creation and spreading of memes. One of the latest flare-ups on Facebook concerned the “Klinger memes” in response to the president’s proposed ban on trans people serving in the military. Perhaps more people I know, whether trans or not, have spoken out against the Klinger memes. I have witnessed many online arguments and defriendings over them. Those in favor of the memes often see them as harmless fun that reference a beloved television character from M.A.S.H. Many are quick to point out Klinger’s fictional existence and the historical context of the show. Critiques of them reifying notions of the “man in a dress” trope used against trans women have been ignored in some cases but fortunately listened to in others. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine that one rather uphold their fondness for a fictional character of decades past than respect the needs of those who tell them of the verbal assaults they endure because of these depictions and of the discrimination, threats, and physical harm they face because of the trope it furthers. Instead, what should more widely circulate are positive representations of actual transgender service members, whether those in uniform or our veterans who wear a graphic t-shirt with the transgender symbol in a pink triangle above the statement, “Transgender Veteran: I fought for your right to hate me” (Equality House, 2016), which has to date approximately 99,000 reactions and 10,000 comments, whether positive or negative, as well as 191,514 shares on Facebook alone.

Allies should remember to listen when a trans person tells them that an image or text is damaging to the community and personally hurtful. A true ally will not demand justification when asked to not share or to remove a post. If an ally wants to learn why something circulating is problematic, wait. It does not take long for media outlets to explain in online articles; or at least give that friend who requested the removal or refrain from sharing time to recover from the pain before inquiring. They will likely volunteer an explanation on their own when they are ready. The trans community needs allies. But it needs allies who listen and who learn what we have to teach them about how to best provide allyship, which includes critically assessing the images and texts circulating on social media before hitting “share.”

|

|

[1] Artivist is a neologism that combines artist and activist to make the connection between a creative expression and its sociopolitical function explicit. Although not all of the content creators would identify themselves as activists, the creative works discussed here were employed to further awareness on social justice issues, including Nike’s video advertisement featuring a trans male activist athlete.

[2] Software and social networking platforms determine the means of expression. Facebook disables the creation of bold or italicized text typed into its text box. Users must rely on typing in all capital letters to produce a sense of emphasis. Typing in all-caps, however, has long been noted as indicating the person writing is shouting their message. Visual emphasis of text that is added to image-based memes most often occurs through use of a bold font and/or all capitalization.

[2] Software and social networking platforms determine the means of expression. Facebook disables the creation of bold or italicized text typed into its text box. Users must rely on typing in all capital letters to produce a sense of emphasis. Typing in all-caps, however, has long been noted as indicating the person writing is shouting their message. Visual emphasis of text that is added to image-based memes most often occurs through use of a bold font and/or all capitalization.

This page is reproduced from "Jumping the Gun: Uncritical Trans Ally Artivism Post‐HB2," by K. Jenkins, 2018, Visual Culture & Gender,13(1), 45-53. Copyright 2018 by Hyphen Un-Press. Reprinted with permission. It can be accessed and downloaded from the publisher here.